When I published my *first book, Breaking into the Backcountry, our family was in crisis. My son had just been born and something was wrong—he cried more than a baby should cry. He never slept. My wife and I had both lost work in the economic meltdown (I’ve written about it here and here and here.) When my box of books arrived in the mail, it wasn’t a cause for celebration. I opened it unceremoniously and pulled one out and thumbed through the pages. Then went right back to trying in vain to comfort my son and find a job.

Publicizing the book fell to the bottom of a long list of more important things. Writing did, too. I managed to do a few interviews and readings but had no bandwidth for any of it. We weren’t sleeping. We had no money.

Even though it had just come out, the book felt like an historical artifact. As though it belonged to someone else.

Eventually I put it in a box inside my mind, one that included all the things I’d lost in my son’s earliest years: sleep, jobs, peace, my writing practice, friends who fell away, the little dream my wife and I had of tenderly holding our baby while he gurgled and cooed and looked around in wide-eyed wonder. The thought of my book (and my identity as a writer) rattled around in that box of loss. Sometimes I took it out just to make myself feel worse. That it was a small loss in the grand scheme of things, not nearly as pressing as other concerns, somehow made it more painful. I felt vain and selfish for thinking about writing at all.

But something strange happened over the next fifteen years. People read the book and kept reading it. From time to time, I’d get an email out of the blue from someone who’d picked it up at the library. Or from a former student who’d read it and fondly remembered our time together. Or from a colleague at a far off university who wanted to teach it in their class. Or from online friends—the only kind I had time for in those years—who posted screenshots of pages and quote-tweeted passages with a link to where it could be purchased. The book had a way of finding people when they most needed it.

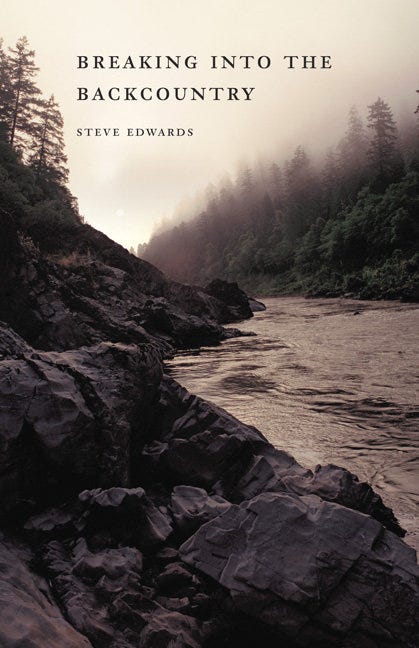

And then just this morning, it happened again. In my role as writer-in-residence at the Concord Free Public Library, I’d gotten on the radar of a local book club in Concord and was invited to join them for a discussion about my book. For an hour and a half today, I got to tell stories about my seven months of “unparalleled solitude” along the federally-designed Wild and Scenic Rogue River in southern Oregon. I got to be a writer sharing his work. And more importantly, I got to hear stories from everyone who came—about their own forays into solitude, their own encounters with bears and wilderness, their own moments of wonder in nature.

The lovely leader of the club had dozens of pages marked with sticky notes. At one point, she read a passage aloud:

One of the unintended consequences of designating places like the Rogue River as “Wild and Scenic” is that it gives us license to continue abusing the places we call home, places we designate “Tame and Ugly”—suburbs sprawling into the countryside, bombed-out inner-cities, industrial factories dumping sewage by the ton into the watershed. It pulls me out of my bliss and perhaps rightly so. On the other side of Rattlesnake Ridge is a world of people and problems, incredible injustice, pain. I can’t pretend that the stench of suffering doesn’t permeate the air even this far outside of town. I can’t pretend that I have any kind of answer or antidote. All I have are the quiet of my days, the gift of which sometimes feels like a terrible burden. What will make me worthy of this experience?

What will make me worthy of this experience? Oh how that question drove my days at the homestead! I remember feeling unworthy all the time—for the beauty around me, the chance to live and write free from all distraction, to be surrounded by wilderness. I was desperate to somehow feel worthy of the gift of it all. The book describes—and hopefully embodies—the answer I eventually came to: that to be worthy of the experience, I needed only to let myself be changed by it. If I wanted to share the beauty I encountered, I needed only to become that beauty.

And I’ll be damned—talking about my book this morning, fifteen years after publication, opened my eyes to something. When my little box of losses starts to feel too heavy to carry, I can ask myself the same question. What will make me worthy of this pain I’ve been given? I have a feeling the answer is the same. To be worthy of my pain, I need only be changed by it. If I want to share the pain I encountered, I need only become that pain. Not to try to shed it or deny it. . .but to live it honestly so that other people in the thick of things might know it’s possible.

What a gift to even try.

So this is me reaching across the years to you, dear readers, to say that I see you trying to hold it all together against the impossibility of your transformations. This is my gentle message for you. Be changed. Be changed. Be changed.

***

*Does the calling Breaking into the Backcountry my first book indicate the presence of a second one? Watch this space for an answer.

The thing that struck me about this piece, Steve, is the idea of an experience’s power to transform. The writer’s job is to convey that transformation. And done well, as you have in the book and in your essays, the experience of reading transforms the reader. It may not even be a “second act” — just a continuation or what Mary Oliver called “one long muscle.”

Love this. Will

Share it with your fan club round here. Thanks Steve!