Out with the dog last night, late, moonlight glinting on three inches of powdery, freshly-fallen snow, I heard a barred owl [insert my uncanny impression of a barred owl’s hooting.] I hear them every January. In the woods behind our house it’s their high season for courting and nesting.

My son heard it, too.

“It was so loud,” he marveled.

My son is 15 and very much a teenager, by which I mean that he’s reached that stage in life in which my presence is a source of constant irritation. My requests for him to do things around the house—Can you take the recycling out? Can you put the dishes away?—are invariably met with: Can’t you? So it means something when, instead of grousing or sighing, he decides instead to share something with me. He’d heard the owl and it startled him. He said it sounded like it was inside his room. He wanted to share that with me.

He knew I’d like that.

And I did.

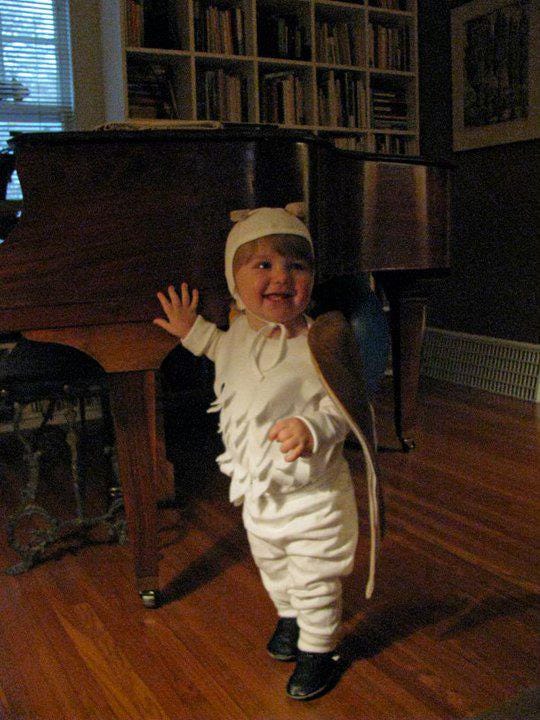

The two of us have a history in owls that he isn’t totally aware of. For one thing, he was an owl on one of his earliest Halloweens—an impossibly cute one.

For another, owls have twice appeared in essays of mine about him and the struggle of his early years. In an essay for Orion called “The Blossoming Child,” the sound of owls served as a reminder that trauma wasn’t the only story I had to tell. In this one for The Manifest-Station, a snowy owl spotted at Crane Beach on Christmas Day rescued me from the slings and arrows of my daily parenting routine.

For another still, there was the year we discovered owl pellets in the backyard and brought them inside to pick apart. Owl pellets are undigested bits of fur and bone an owl coughs up through its beak like a hairball. They are oval-shaped and gray like dryer lint. We put newspaper on the kitchen table and with a pair of tweezers carefully pulled the pellets apart, loosening snags of tangled hair and revealing, in one, a perfectly intact mouse femur. I remember imagining the mouse scurrying under the snow by the forsythia. The owl’s silent glide and outstretched talons.

My son remembers none of this. But I like to think that the experience is part of what made him want to tell me about the owl he heard last night. I like to think that every walk through the woods we’ve ever taken somehow resides in him still, not as a memory but as something more, an essence, a residue of my love for him, of my desire for him to feel at home in the world. Life takes so much from us, brutalizes us, strips us down for parts. Everyone we ever love will die. No getting around it. To feel at home in a world like ours—to accept it exactly as it is and not how we wish it were—is our only refuge.

The poet John Haines speaks to what I mean in his poem “If the Owl Calls Again.” I remembered it at the end of the night, at bedtime, when I told my son it was lights out and he shrugged grumpily but after a moment capitulated. I lay in bed, in the dark, the whole house quiet, and remembered:

If the Owl Calls Again at dusk from the island in the river, and it’s not too cold, I’ll wait for the moon to rise, then take wing and glide to meet him. We will not speak, but hooded against the frost soar above the alder flats, searching with tawny eyes. And then we’ll sit in the shadowy spruce and pick the bones of careless mice, while the long moon drifts toward Asia and the river mutters in its icy bed. And when the morning climbs the limbs we’ll part without a sound, fulfilled, floating homeward as the cold world awakens.

I had never thought of the poem as a parenting poem, and it’s probably a stretch to do so, but I can’t help it. In my head it almost reads as: If the baby cries again…I’ll rise from my bed and go to him. In my son’s earliest days, when he was so very sick, that’s what I did, night after night. I rose from bed and went to him, changed him, held him, swaddled him, sang in his ear. I’m not over it. I’ll never be over it. Those years are a broken shard of undigested bone in my throat.

What I like about the poem, then, is its refusal to make a point or come to some conclusion or insist on a meaning beyond being exactly what it is. It is happy enough to live wholly inside its conceit: If the owl calls again at dusk, the speaker will take wing and “glide to meet him.” The promise of that is enough. Let the tawny eyes search. Let the long moon drift toward Asia. Floating home in the dawn, the speaker and the owl are fulfilled. On our best days, that’s my son and me.

I thought about that last night, that fulfillment, in the dark, drifting off to sleep and listening into the darkness for an owl.

This is so beautiful. As my youngest has been dealing with the wildfires in L.A. this week all I could hope is that every walk I've taken with him as a child, is residing within him still as well.

Thank you for these words and wisdom.

It’s too easy to ‘heart’ things on Substack but I really really ‘heart’ this. Beautiful.